READ THE PDF-VERSION HERE

Next year, I will celebrate Christmas on April’s fool day, and give Easter presents on Halloween. In my 2014 agenda, I have noted to skip Christmas holiday. This is my way of protesting against the fake and commercialized institutional holidays that program our feelings, and wear out our feet running to shops to buy the appropriate props and gifts. I definitely don’t want to share in this artificial sentimentality cemented with consumerism.

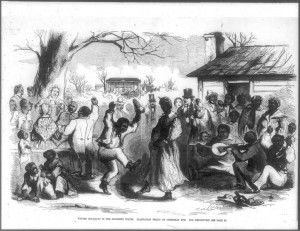

The blues people’s ancestors, the enslaved, did not have this freedom to disregard Christmas. On the contrary, if they did not participate, it was because they were punished. If they did not put on a happy face in front of their master who organized Christmas for them, they ran a serious risk of being punished. Christmas holiday was another way in which their bondage cruelly manifested itself. Yet, still today, both the popular and scholarly view on the slaves Christmas are markedly benign and wrapped in sentimentalism presenting Christmas as a time of pure merriment for the antebellum African American. The engraving below, reproduced from an article on Christmas in the United States in the January 1863 German magazine, Der Bazar, is only one illustration of this false image of history.

I set aside considerations about the place of a Western religious “holy” day in the African American culture. It is a complex relation of which the discussion would lead us too far. Suffice it here to say that, as we will later see, the slaves incorporated – as in other realms of their social life – African elements in “their” Christmas customs. There was thus far from a one way white to black impact[1]. In what follows, I want to argue foremost how a slaves’ Christmas can only be fully interpreted if it is approached as another instrument by which power relations were confirmed and strengthened. The joyful sounds of the violin and the banjo, and the exuberant dancing veiled a reality of subtle mechanisms of social control, read: oppression. I want to make my point along three features of Christmas: (a) the work interruption, (b) the exchange of gifts, and last but not least, (c) the dinner table.

However, let me first quickly sketch the historical background of Christmas in the United States[2]

Curiously, prior to the Civil War, North and South America were as divided on the issue of Christmas as on the topic of slavery. Reportedly, Christmas set foot on American shore in the 1500’s coming along with the Spanish Roman Catholic colonists on the South Atlantic seaboard. While it took root in the Southern states, it met with strong resistance in the Northern puritan states where Christmas was considered as pagan and sinful. Thanksgiving Day was seen as much more appropriate. Boston even outlawed, between 1659 and 1681, the celebration of Christmas, fining anyone who exhibited the Christmas spirit five shillings. It was only in 1870 that Christmas was declared a federal holiday. By the time of the Civil War, the Southern states had however already firmly embraced the Christmas celebration as a steady element of their social life, both in rural and urban areas. Four decades before it became a federal holiday, three slave states had instated Christmas as an official holiday.

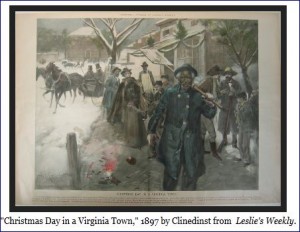

It was among the Southern class of owners in the antebellum years that today’s features of Christmas in the United States took shape. Special food was prepared, and the whites went shopping for gifts and decorations for the house. Church was attended and carols were sung.

In many regions the slaves were integrated in the activities and festivities. Early reports on the involvement of bonds people in the Christmas operations are confirmed by later studies showing that Christmas became the one holiday shared by blacks and whites. It was the day that barriers between the owned and the owners were lowered. Cato, a former Alabama slave, told a Federal Writers Project-reporter when interviewed in the 1930’s[3] how “Christmas was the big day.” “Presents for everybody, and the baking and preparing went on for days”, she continued. “The little ones and the big ones were glad, ‘specially the nigger mens, ‘count of plenty good whiskey. Massa Cal got the best whiskey for his niggers.” Jenny Proctor, also a former slave from Alabama, added that at Christmas “Old Master would kill a hog and give us a piece of pork.”[4] Another former slave described the “big time” also in terms of “presents for everyone.” “The white preacher talk ‘bout Christ. Us have singing and ‘joyment all day. Then at night, the big fire builded, and all us sot round it.” [5]

CHRISTMAS LASTED AS LONG AS SWEET-GUM OR PINE KNOTS

Jenny Proctor, during her interview in the FWP-project, also alluded to the duration of the work interruption at Christmas.

“…and the way Christmas lasted was ‘cording to the big sweet-gum backlog what the slaves would cut and put in the fireplace. When that burned out, the Christmas was over. So you know we all keeps a-looking the whole year round for the biggest sweet gum we could find. When we just couldn’t find the sweet gum, we git oak, but it wouldn’t last long enough, ‘bout three days on average, when we didn’t have to work. Old Master he sure pile on them pine knots, gitting that Christmas over so we could git back to work.”[6]

This summarizes well the ambivalence around the work interruption that was granted to slaves on the Christmas occasion. Sweet-gum wood, preferred by the slaves to put on the fire place is known to dry very slowly and to burn long; pine knots, on the contrary, feed the flames and boost the fire in a short period.

In this story, Jenny Proctor recalls the tradition, observed in some places, of the “Yule log” burning on the master’s fireplace in the Big House. “Yule” refers to the celebration of the longest night of the year and to the turn of the season as celebrated in the original heathen feast that was later transformed by Christianity to Christmas. The “Yule log” was an extremely hard log placed to burn in the fireplace during Christmas time. Today, it is associated with for instance the log-shaped Christmas cakes, popularly known by the French speaking among you as the ‘Bûche de Noël’. The log was, as the former slave Proctor tells us, the hourglass counting the days of Christmastime, and thus of work interruption. Booker T. Washington also entrusts us that slaves would search for the biggest, toughest and greenest hardwood tree they could find, and would then soak it into water for the entire year.

The slaveholder however had all interest in having the fire burn as fast as possible, putting, as Jenny Proctor mentions, pine knots on the fire place.

There is considerable disagreement on just how long the Christmas break lasted. Some sources reveal that Christmas’ break lasted as long as a week, when the slaves could come together, meet family and friends, tell stories, sing and dance and hence strengthen their communal spirit. Other sources advance that the work interruption did not last longer than two to three days; still others put forward a period somewhere between three and seven days[7]. The duration aspect of the Christmas break is of significant importance, but does not always receive the appropriate attention in the literature. Seen from the perspective of the slaveholder, any work interruption was a major event because it had an economic impact on his “chattel property” investment. It is not hard to imagine that he meticulously counted the number of days of interruption, keeping them as small as possible. Pine knots came to his help when the sweet-gum wood or soaked oak burned too long. Each day was a loss. From the perspective of the slave, it is not difficult to argue that each day freed from toiling was a treasured day. The difference between a two or a three day break, let alone a full week, was tremendous.

Though all documentation has not yet been thoroughly examined, it is safe to say that there existed a considerable variation between regions and individual slaveholders with respect to the number of days slaves were allowed to celebrate Christmas. The granting of a day off was far from an arbitrary decision. Moreover, it would be wrong to assume that all slaves benefited from the slaveholders’ Christmas generosity, if we can call it that way.

There is evidence that economic conditions did prevent the slaves on some plantations to benefit from work interruption. On Louisiana sugar plantations, for instance, the harvest and the production process often made any break impossible, and if harvest came late there was no room for pleasure. The denial of a Christmas break was also an instrument of punishment for earlier misbehavior or for his productivity over the year that the slaveholder defined as insufficient. Even in the late antebellum period, some slaveholders refused any Christmas break. P.L. Restad quotes an ex-slave from Virigina for whom Christmas “was just lak any other time wid de slaves.” Moreover, the master of this slave had waited until Christmas to execute his punishments for “bad” behavior during the past year. He chained two of his slaves during 1836 Christmas, one “for general bad conduct”, the other for “bad conduct during cotton picking season.” In 1839, he intended to exhibit another slave during Christmas on a scaffold in the middle of the quarter, “with a red flannel cap on.”

After another year of harvest, Christmas was indeed for many planters the moment when they drew up the accounts and evaluated the efforts deployed by their slaves in the past year. The state of the plantation tools was inspected and the right to a break of the work routine was conditioned by the outcome of the evaluation. If the master was displeased, he could also hold back the possibility of the slaves to visit their relatives or friends. Joyner reports: “Tool inspection had taken place each Christmas day since 1844. An extra ration of rice, peas, molasses, and meat, equivalent to a week’s ration, was given to ‘all who are not defaulted in showing their working utensils and who have not been guilty of any ‘greivous’ (sic) offence during the year”.

The denial of any Christmas break is confirmed by a number of interviewees in the FWP-project when some thirty of them declared that they never celebrated Christmas at all, and a number of them did not enjoy any holiday at all. One of them testified: “Christmas? I don’ know as I was ever home Christmas. My boss kep’ me hired out.”[8]

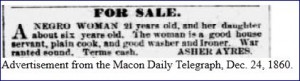

There is furthermore evidence that in some cases even the slave trading operations just continued during Christmastime. For some domestic slave traders, Christmas was no reason to interrupt their activities, and they did not hesitate to break up families and transport the slaves, chained together, over the frozen roads to their new owner. One slave report mentions that on December 31st 1859 some three thousand slaves were awaiting their sale on the New Orleans market. A case has been documented of a boy who was bought in December and was given to the mistress of the “big house” as a Christmas gift.

In any case, Christmas did not stop most of the planters who hired out slaves from making the arrangements for the new annual contracts that would start on January 1st, also known as “Heartbreak Day.” The psychological terror and emotional anxiety of being sold to new owners, with a possible rupture of family and children, was for many of the enslaved a harsh reality spoiling any possible feeling of joy. Harriet Jabobs, an American writer-abolitionist and escaped slave phrased it as follows: “Were it not that hiring is near at hand, and many families are fearfully looking forward to the probability of separation in a few days, Christmas might be a happy season for the poor slaves.” However, only a few days separated “Big Times” and a “Heartbreak Day” which quickly drowned any jubilant Christmas mood, whether real or forced.

Finally, it can be questioned whether the romantic Yule-log tradition described above was as wide-spread as it is sometimes suggested. The scattered stories on slaves cleverly looking for the log that would burn as long as possible on the “massa’s” fireplace do not support the conclusion that the practice was generalized in the slave states.

All in all, the romantic vision of a Christmas break for the antebellum enslaved African American population thus needs serious qualification. While for some Christmas doubtless meant a break in the toiling for one or a few days, there are also indications that for others it was business as usual. On some plantations Christmas was nothing more than the day when the planter was a bit more tolerant and less lavish with the whip than during the rest of the year.

SMILE AND BOW FOR THE MASTER’S GENEROUS GIFTS

Christmas is associated with the exchange of gifts, seductively displayed under the sumptuously decorated tree. It is hard to escape the social pressure of participating in the ritual of offering family and friends the presents they had been eagerly waiting for all year. The social expectancy is that strong that it transforms itself in a merciless consumerism that draws unprivileged even farther in dire straits.

For the bonds people who shared (some of) the Christmas rites with their owner, the giving and taking of “presents” was also part of the usage and it is fascinating to see the different usages involved.

Slave parents reportedly did everything they could to bring a smile to the face of their children who expected to find gifts in their stockings in the parents’ shack. Despite their predicament, slave parents surprised their children with pieces of candy and ginger-cakes, and occasionally, extra clothing. Harriet Jacobs remembers how slave mothers tried to brighten the hearts of their little ones. Once, she witnessed two young children proudly and cheerfully running in the street with their new suits on, fashioned by their mother. However, it was a bittersweet sight: their mother had meanwhile been imprisoned and was deprived of sharing the delight sparkling in her children’s eyes.

More interestingly, though far from warmhearted as between parents and children, is to witness the various gift rituals between the slave and his owner. On some plantations, the slaves were allowed to come to the main house, which was often the only time in a year they could visit the master’s house interior. Sometimes, a special Christmas supper was prepared for the quarters as well as for the big house. The slaves dressed in the best clothes they could gather to sit on a dish consisting of luxurious foodstuff they could enjoy only once a year. On other plantations, the “master” and his family went over to the slave quarters to exchange greetings, to witness their dancing, and to present gifts.

The gift exchange was sometimes embedded in the Johnkannaus tradition (also known as John Koonahs, Jonkonnua, John Canoe and John Kanhaus). Every child rose early on Christmas morning, writes Harriet Jacobs, to see the athletic men, “in calico wrappers () with all manner of bright-colored stripes” who visited white households in the community, performed dancing and singing on the white folks’ doorsteps waiting to receive donations which they would take home to their families. “Cows’ tails (were) fastened to their backs, and their heads (were) decorated with horns”. Rambling from door to door, they were beating a box covered with sheepskin (a gumbo box), striking triangles and jawbones, accompanied by bands of dancers. By hundreds, the masked men turned out early on Christmas morning and went round until noon. In exchange for their entertainment, they received a penny, or a glass of rum, which they would however not drink while they were out, but would carry home in jugs. Their repertory had been carefully prepared in the preceding weeks and often consisted of new songs.

Unlike the European rooted ‘Yule log’, the Johnkannaus ritual continued a tradition from the West Coast of Africa and that with the African Diaspora was spread to the West Indies and the southern coast of America. It was an African flavor added to a Western ritual.

The gifts were material and immaterial. The former could consist of food – I will come back on this more in detail later – and Christmas was the time of the year when (some) planters allowed the slaves to drink as they wanted. Slave reports mention the provision of liquor as whiskey, eggnog, and to a lesser extent brandy, cider, wine and beer. Liquor was an important aspect of the happening, but the quantities distributed differed greatly from plantation to plantation. Tobacco was also on the list. For children there was candy. Clothing items were too a recurrent gift: shoes, socks, pants and frocks, hats, ribbons, handkerchiefs to tie up the women’s and girls’ hair… Occasionally there were “surprise” gifts in the form for instance of a Barlow knife for the boys.

Only rarely, money was given. The owner could throw coins among the slaves, to the great excitement of the children. Christmas was also the only period in the year when slaves– in a few communities – were allowed to sell the products fashioned by their handicraft and could keep the money. Some narratives mention slaves who over the years collected enough money to buy their freedom.

The concessions sometimes granted to slaves during Christmas can too be reckoned among the gifts stemming from the planter’s “Big Time” Christmas generosity. Wilma King[9] quotes a Northern observer who in the 1850′s travelled in the South and called the Christmas celebration “genuine Darkey amusements in excels of originality”. Though dancing was performed also at other times during the year, as on Saturday evenings or during corn husking, it gained an extra dimension during Christmastime when the planter interrupted the daily rut of raw labor during one or several days. The dancing was also less restricted during the holiday and lasted longer. Banned as threatening in normal periods, even the presence of drumming has been witnessed during the slaves’ Christmastime dancing.

Christmas was for some the time to have a ball that started in the afternoon and could last until the next morning, sometimes during several days. Parades, songs and elaborate performances, mixing European and African elements, characterized the slaves’ Christmas. The interruption of labor also freed time for playing ball, wrestling and foot-races. It was on the Christmas festival that slaves “lavished their most energetic efforts”[10].

It has been documented furthermore that Christmas was often preceded by slave marriages, and that it was not uncommon to have several weddings at the same time and place. It was also a popular time for young slave couples to become engaged. Note though that these “weddings” had no legal status whatsoever, and were a mere ritual (“jumping the broomstick”) that the slave-owner tolerated during Christmastime, rather than granting dedicated time-off during another period because this would imply an additional interruption of labor.

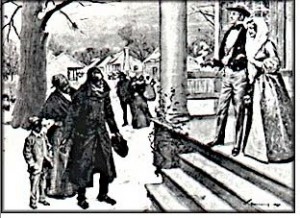

Christmas could moreover be the time when slaves received the privilege to go to town or to visit relatives or friends at neighboring plantations. The planter handed out special passes that let slaves stay away from the plantation for a few hours, a day or sometimes even a few days. Many husbands, wives, parents and children saw each other only once a year at Christmastime. The passes created the opportunity for marriages to take place between slaves from different plantations.

Even disregarding whether the planter engaged with honest feelings of generosity or not, the gift exchange ritual was far from socially neutral. As it has been demonstrated[11], gift giving is a relevant process in terms of the maintenance of the individual’s identity: by accepting a gift, we implicitly confirm how the giver feels about our ideas and desires. The gift giving is moreover a technique that contributes to the maintenance of social relations, and is in that sense a component of social stability and existing power structures. This knowledge puts some aspects of the Christmas rites of gifts in the antebellum South in a different light.

It explains why the direction of gifts was almost exclusively one from white to black. The instances of slaves giving gifts to their master have been very rare[12]. There are some narratives which for instance mention slaves making baskets or walking sticks for their master and for the older white men and women, but a more common practice of transfer of gifts from black to white would have questioned power relations.

The game of “Christmas gif”, still a tradition today and already observed in many Southern regions during slavery can be seen in the same perspective, and presents a cynical form in which the power relations seemed temporarily to be reversed, only to function eventually as another medium to strengthen the slavery institution. In the surprise game black and white would compete on this holiday to be the first to shout “Christmas Gif” !’ The loser was always the white who had to pay a forfeit of a simple present to the black winner to be released from the temporary “catch” by which the black held the white “imprisoned”. Clearly, winner and loser were fixed role models that were molded on a racial basis.

How important the gift functioned in the cruel confirmation of the slavery has been illustrated by testimonies of planters, who in times of economic distress and shortages did everything they could to continue the existing gift-giving ritual and to avoid to show up on Christmas with empty hands when the slaves caught them in the “Christmas gif” game. One planter, who was not able to provide the slaves with the traditional “present” of shoes, gave lower quality food to avoid the embarrassment of having to admit his economic plight in the face of his slaves[13].

This is not to say that the shoes he would have otherwise offered were a luxury item. The shoes would probably have been highly needed. The clothing items slaves received from their masters at Christmas were mostly only the yearly allotment of clothes they were anyhow entitled to according to the customs ruling the maintenance of “chattel property”. Only those who had been particularly productive during the year were rewarded with some extras. As was the case for the duration of the work interruption, the gift giving could be turned into an instrument of reward or punishment when the enslaved saw his gift suppressed for supposed misconduct or lack of sufficient labor efforts.

Depriving the slave of a pass to visit family and friends on other plantations was one of the repressive instruments that came on particularly hard knowing that Christmas was frequently the only opportunity in a year for reunion. For the slaveholder, the suppression of a pass was a double advantage. It not only functioned as a strong argument to convince the slave that he’d better stick to his obligations, it also reduced his fear of escapes and rebellion that accompanied the indulging of some mobility. Frequently, Christmas came with rumors of slave uprisings and with slave escapes which were dealt with by reinforced security measures. The dreaded slave patrollers worked overtime on Christmas holidays.

This leaves us also to wonder how Christmas must have been really felt like by both black and white, and to which extent the outer veil of joy – if at all present – was no more than a charade. On one side, the white played the role of the generous planter, only to validate his dominant position, but deep down he feared that social stability was in danger. On the other hand, the slave had to put on his happy Christmas mask, to smile and bow for the generous master because the apparent absence of gratitude and delight came at the real risk of serious sanctions. Happiness was an obligation, not a right. And ultimately, we can only guess how the slave must have felt when confronted with the lowering of the barrier with his master. I can imagine that the temporary breach in intimacy was not necessarily welcomed.

PIG FEET OR POSSUM

Gifts were central to Christmas; so were food and drinking. Many narratives on antebellum Christmas illustrate the custom of the master setting up a long dinner table in the house, filled with food that must have been delicacies for the bonds people. The preparations of the dinner table, sometimes made weeks ahead, were already a welcome break in the plantation life. Booker T. Washington remembers how hogs were killed and butchered, ham was smoked, and wood was brought in, cut and stacked high in the wood-house. He vividly sees the hogs hung in long rows on the fence-rail, ready to be cut up (…).

Christmas was the time when the slaves could have butter, eggs and sugar, and choice cuts of meat. Roast chicken, ham, squirrel and possum could be on the menu, with side dishes that might include squash, greens cooked with ham hocks and salad greens or ashcakes (boiled cornmeal, sweetened with molasses and wrapped in cabbage leaves). Barbecue was sometimes served (which was a way of consuming the recently butchered meat before it spoilt). Slaves could bake a cake, or made sweet potato pie. Homemade wine and plenty of liquor – whiskey, eggnog and other spirits – provided by the slaveholder accompanied the food[14].

In short, Christmas was the day when temporarily the quality and quantity of the slaves’ food were altered. It broke the monotony of an otherwise poor food pattern.

Though no definite conclusions are yet available, and there seemed to exist considerable regional variation and differences from plantation to plantation, the available documentation on “what slaves ate”[15] demonstrate beyond doubt that for many of them the standard diet was poor to very poor. It is no surprise that pork and corn, being plenty available because easy to keep and produce, were the major components of the slaves’ food. Pork’s consumption was many times higher than in Europe, and corn was then more valuable than gold. In the rice growing regions of the upper Southern coastal states, rice was evidently an important item on the menu. These ingredients were also dominant in the white’s menu, but with a substantial difference: the slaves’ menu was both in quantity and quality generally below standard, and unvaried.

The heavy reliance on corn – for some African-Americans it was the only food – in all its different preparations had some major nutritional drawbacks showing in the form of diseases as pellagra, a vitamin deficiency disease that is still frequent today in developing countries. As for pork meat, only the poor cuts and leftovers reached the slaves cooking pot: jaws, ears, tails, feet, organs, and chitterlings. Chicken feet were a welcome variation.

However, as was the case for other aspects of their social and cultural life, the enslaved showed immense creativity in adapting to their plight, thus showing a remarkable continuity with features of their original culture combining the ancestor’s experience with what they witnessed in the big house’s kitchen. The artful use of spices turned even the most meager left over of the pork into delicacies, inspiring eventually also the master’s menu. The ration provided by the slaveholder was furthermore supplemented with food they stole from either their owner or from another plantation, the latter act being ultimately welcomed by their owner because it meant that he could cut on the ration he provided for his slaves[16]. More importantly however is the observation that slaves also gained some control on their food pattern by hunting, trapping, fishing and gardening. The hunting and fishing on Sundays enriched the diet with catfish, sturgeon, small birds, rabbit, duck, raccoon, opossum and squirrel. If the slaves were allowed some gardening activity – another way for the owner to cut out expenses – vegetables (lettuce, black-eyed peas, cucumber, radishes, sweet potatoes, collards, melons, …) were a more than necessary complement to the otherwise poor and monotonous diet.

These practices may not obscure the fact that the control over food and distribution lay ultimately in the hand of the planter. Documents show that he paid attention to the slaves’ feeding pattern, but mainly if not exclusively from the perspective of the link with health issues, and thus in view of safeguarding the productivity of his property and its market price. Elder slaves and children definitely received less attention compared to the productive labor force that – according to agricultural journals of planters – obtained just enough to keep it functioning. Food was an element of the production cost and its allotment was thus subject to careful, calculated consideration. Its use as a means of rewarding and punishing remembered the slave that at the end of the day it was the owner who held the strings. The group in control of food is also the group who holds power, and has the instruments to determine the life quality of the subordinate.

The exceptional allocation of extra portions and of better quality food at Christmastime – or its retention in case of punishment – is another illustration of the functioning of this prewar power structure. The calculated and self-interested thoughts behind the pageantry did not go unnoticed in some slaves’ eyes. Many planters were for instance during Christmastime, but under their strict supervision particularly generous with strong liquor even to the point of the slaves becoming totally loaded. The argument was then advanced that, all things considered, the slave was better off in his state of bondage, because he needed the firm hand of a ‘caring father’ to keep his life on the right track. Freedom would only drown the slave in a permanent state of intoxication and would bring him on the road to complete debauchery. This is how Francis Frederic[17], an escaped slave, tells it:

“About Christmas, my master would give four or five days’ holiday to his slaves; during which time, he supplied them plentifully with new whiskey, which kept them in a continual state of the most beastly intoxication. He often absolutely forced them to drink more, when they had told him they had had enough. He would then call them together, and say, “Now, you slaves, don’t you see what bad use you have been making of your liberty? Don’t you think you had better have a master, to look after you, and make you work, and keep you from such a brutal state, which is a disgrace to you, and would ultimately be an injury to the community at large?” Some of the slaves, in that whining, cringing manner, which is one of the baneful effects of slavery, would reply,“Yees, Massa; if we go on in dis way, no good at all.”

“Thus, by an artfully contrived plan, the slaves themselves are made to put the seal upon their own servitude. The masters, by the system, are rendered as cunning and scheming as the slaves themselves.”

The slaves’ joy was bitterly used against him to justify the institution of slavery, and Francis Frederic and other slaves were well aware of the mockery involved.

THE DUTY OF CHRISTMAS

I praise myself happy that today’s Christmas obligation and the accompanying stress of visiting family and buying gifts, and sitting long dull hours at a ridiculously decorated dinner table, is just a social constraint and harassment from which I have the luxury to escape, if I want. The antebellum African-Americans who lived in bondage did not have this liberty.

Christmas was not a social event from which they could break loose, any more than they could from their chains. If the planter allowed one or a few days of interruption from the back breaking burdens of daily routines, if he engaged in the expected gift giving ritual, and draped the table with some decent pork meat instead of throwing the usual pig tails or ears in the slaves’ troughs, the slave did not have the liberty to refuse his owner’s generosity. Their smile and gratitude were an indispensable part of the global merry picture, and were a necessary counterpart of the slave-owner’s strategy of offering Christmas as a token of his paternalistic role as a good “father”, as a way of affirming there was no other fate for his black property than belonging to him. If the slave did not play the content property, punishment was his fate. Exceptionally, when the owner showed indulgence by attributing the continued sorrow despite Christmas to other conditions than slavery, for instance to a temporary poor health, the slave could hope to evade the whip.

Ironically, one could argue that not only the enslaved but also the slave holder was imprisoned by the Christmas ritual, and that also for the latter the acceptance of a slave holiday was an obligation and not a warmhearted gift. Not granting a holiday to the slaves was even more dangerous. Several planters disliked Christmas for interfering with their working schemes. One planter noted in his diary in 1845 that he was “getting tired of Hollidays, negros want too much.”[18] Another one wrote one Christmas: “I only wish the Negroes were at work.” Still another wrote in 1840 in unambiguous terms: “Christmas is over (blessed be the lord) and tomorrow we go to work.”

For many planters, the end of Christmastime was also the end of a dreaded period because they feared that the concessions granted to slaves would not only create the material opportunities for escapes, but would also ignite resurrections. The joy of Christmas was troubled by the fear of slave revolts, and it is no coincidence that in this year’s period a high number of rumored slave plots have been recorded. The threat of uprisings was countered by reinforced controls, and the nervous tension no doubt explains some outrageous disciplinary measures observed at Christmas, like the one narrated by former slave Frances Patterson, who recalls her master beating her young brother so badly on Christmas for some presumed negligence when watching the cattle that the boy bled to death.

Thus, the usual benign image of a slave’s Christmastime may not cloud the sorrow and oppression which framed the ritual and which gave it a bittersweet taste as one of the de facto instruments to maintaining slavery. It was a safety valve that took the strain away from this “peculiar institution”, as it was euphemistically called. The safety valve worked on both sides of the power structure. For the white class, it helped to sooth the consciousness. During the annual paternalistic Christmas ceremony, the planter could bath in his feelings of benevolence. For the enslaved, Christmas could after all mean a temporary release of discontent, anger and frustration. While at the same time creating fear for resurrections in the planter’s mind, Christmas celebrations also had the capacity of choking a potential rebellious spirit.

In short, the light from the burning Yule log or from the fires outside at Christmas brutally highlighted the lack of freedom. Fredrick Douglas, ex-slave and later active abolitionist, portrays Christmas as part of the ruling moral economy in which the relative “liberty” granted by the slaveholder was but a psychological tool of subjection that allowed him to demonstrate, once more, that slaves were a happy bunch of people.

Enjoy Christmas, if you still feel like it! I will now put on Miles Davis’ 1962 record “Blue Xmas, To whom it may concern”, with lyrics from Bob Dorough:

Merry Christmas

I hope you have a white one, but for me it’s blue

Blue Christmas, that’s the way you see it when you’re feeling blue

Blue Xmas, when you’re blue at Christmastime

you see right through,

All the waste, all the sham, all the haste

and plain old bad taste

Sidewalk Santy Clauses are much, much, much too thin

They’re wearing fancy rented costumes, false beards and big fat phony grins

And nearly everybody’s standing round holding out their empty hand or tin cup

Gimme gimme gimme gimme, gimme gimme gimme

Fill my stocking up

All the way up

It’s a time when the greedy give a dime to the needy

Blue Christmas, all the paper, tinsel and the fal-de-ral

Blue Xmas, people trading gifts that matter not at all

What I call

Fal-de-ral

Bitter gall…….Fal-de-ral

Lots of hungry, homeless children in your own backyards

While you’re very, very busy addressing

Twenty zillion Christmas cards

Now, Yuletide is the season to receive and oh, to give and ahh, to share

But all you December do-gooders rush around and rant and rave and loudly blare

Merry Christmas

I hope yours is a bright one, but for me it bleeds

[1] It is also interesting to note that it is only since the Civil Rights movement in the 1960’s that the first specific pan-African and African-American holiday was introduced at the initiative of Maulana Karenga, an African-American professor, activist and author. The celebration “Kwanzaa” – a name derived from the Swahili “matunda ya kwanza”, meaning first fruits of the harvest – is a week-long celebration that starts on December 26th and lasts until January 1st. Though it is not meant as a replacement of Christmas, it has gained popularity in the last decades as a way for the African-American community to reconnect with the African cultural and ideological heritage.

[2] Inspired by Bigham and May, The Time O’ All Times, 2012, and: http://www.thehistoryofchristmas.com/ch/in_america.htm

[3] B.A. Botkin (ed), Lay my burden down, 1945, p. 96

[4] Idem, p. 102

[5] Idem, p. 248

[6] Idem, p. 102

[7] Bigham and May, The Time O’ All Times, 2012

[8] Idem, p. 277

[9] Wilma King, Stolen Childhood: Slave Youth in Nineteenth-Century America, 1998

[10] James Walvin, Questioning Slavery, 1996

[11] See for instance: Barry Schwartz, The Social Psychology of Gift, American Journal of Sociology, 1967, vol. 73, n° 1.

[12] Bigham and May, The Time O’ All Times, 2012, p. 274

[13] Idem, p. 276

[14] http://christmas.celebrations.org

[15] The documentation on the slaves food pattern is drawn foremost from: Herbert C. Covey and Dwight Eisnach, “What the slaves ate”, 2009

[16] Taking food from the owner or from another plantation was not considered by the slaves as “stealing”, but as a matter of pride, of gaining control.

[17] Slafe Life in Virginia and Kentucky, 1863

[18] Bigham and May, The Time O’ All Times, 2012, p. 280