In his article “From Blues, The conflict of Cultures” (1961), Janheinz-Jahn convincingly argues that if one reads the blues texts carefully, without any prejudice, they are all only exceptionally about melancholy. Yet, blues is associated in our minds and in our language with melancholy; when we have the blues, we mean that we feel sad, that we think about what we don’t have and that we feel pain. In the same image, we see the blues musician as a loner who sings about the woman who has left him, about his feelings of sorrow, about his longing for better times.

This melancholic interpretation is however false and does not correspond at all with the true spirit of the blues? But, where does it come from?

First of all, as the author contends, we need to see the blues song as a descendant of the old ballad form, which on its turn has its roots in the African culture, in the tradition of the African fables and tales. The latter deal with all aspects of daily life, but one needs to see beyond the images and facts that are their immediate subject. They have a highly symbolic nature and always tell a story that goes beyond the individual, but that is important and relevant for the group. He quotes the example of the Boll Weevil Song, on which I dedicated a post on my blog some time ago. It would be wrong to see the blues singer as somebody who expresses his own personal feelings of pain and transfers them to his audience. He does not sing about his own experience before his audience, instead he translates the feelings of his audience. He is its spokesman. Janheinz-Jahn : “It is not the personal experience that is emphasized, but the typical experience of all those rejected by society in the Negro districts ().

I’d rather drink muddy water, sleep in a hollow log,

dan to stay in dis town, treated like a dirty dog.”

The melancholy of the blues is only a camouflage. We need to look through this outside layer, listen through the double meaning and hear the sarcasm, the tragic, the mocking, the drama, the accusations and often the crude humour that is underneath the outside surface.

He further argues that, in line with the African tradition, a song does not serve to express a mood; it is instrumental in creating a mood. Just as work songs were not an aid to the work, but the work served the song, one needs to interpret a blues song not as the reflection of a mood, but as a medium that shapes the mood, that wants to evoke a feeling, tell us something about how the group thinks and feels.

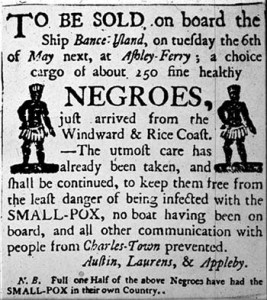

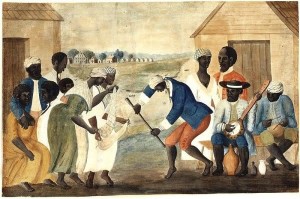

The misunderstanding about the blues as a melancholic song stems from the social conflict between the plantation owners on the one hand and the abolitionists who wanted to free the slaves on the other hand. The plantation owners put forth the image of the happy slave who enjoyed his work so much that he was constantly singing and dancing (we see this image also in the minstrelsy songs). The abolitionist reacted by creating the image of the sad slave singing melancholic songs. His cultural image of the slave was one of a poor, helpless creature that longed for freedom and expressed his sorrow in his songs. However, this cultural image also presented the slave as a human being that needed liberation, not as one that would rebel and fight for his own freedom. The abolitionist’s view was paternalistic; the slave was a melancholic being who needed help…from the white. His view was that of a passive individual, not an active one. The slave needed to be freed in a pacific way; he could not be stimulated as an agitator.

The author concludes that both views of the slave and his musical culture are distorted and have led to false interpretations about the true spirit of the blues. “Slaves sing to make themselves happy rather than to express their happiness through singing. The blues do not arise from a mood, but produces one. () The spiritual produces God, the secularized blues produce a mood.”

I would like to add, from my side, the thought that it is no coincidence that blues emerged on the field of the failure of the Reconstruction and Post-Reconstruction. Blues originated in the first generation of African Americans who were not held as slaves, but this generation had not yet an outlook on something better. The aftermath of the liberation had not fulfilled their aspirations. Blues at the same time summarizes this failure and expresses the hope for a better future, but often in an sarcastic way that reflects the on-going social disintegration that didn’t hold any better perspectives than the one they had experienced in the past. As no other medium, blues are the expression of this unique combination of pain and hope that many felt, but a hope that proved to be in vain. Blues was not the heartbreaking cry of an individual, it was the cultural expression of a whole oppressed social class.

I would like to conclude with this quote from S.C. Tracy in his book : “Write me a few of your lines” (1999) :

“It is difficult to conceive an art form that more brilliantly and directly expresses the angst and the optimism of the twentieth century, in lyrics and music that have become more pervasively influential, and in spirit more expressive of the emergence of vernacular culture to its significant level of importance, culturally and socio-politically, than the blues”