The study of history is often big fun because it leaves room to speculate in terms of “what if”. For instance : “what if” the African Americans would have had full control on their music production in the 20s instead of being “colonized also in wax”? What if for instance the Black Swan Label or some of the other black owned companies in the recording business (Sunshine label, Chappelle and Stinnette’s C & S Records, Winston Holmes’s Merrit Records) (W.H. Kenney, 1999) would have been commercially successful? Would the history of (black) music have evolved in another way? Intriguing question, no?

Equally fun is to open bets on how things might have run if certain coincidental events which have been the trigger of major developments would have turned out another way. What if for instance on Tuesday August 10th 1920 Mamie Smith would not had been able to be a stand in for Sophie Tucker in the Okeh recording studio in New York? Sophie Tucker was scheduled to have a session but had fallen ill, and a certain Perry Bradford had succeeded in convincing the studio boss Fred Hager to replace the white vaudeville artist with the black vaudeville singer Mamie Smith. Mamie Smith is commonly seen as the first black singer, using a totally black backing group (her “Jazz Hounds”) to record (with huge commercial success) a blues song (though some will question it whether it can really be considered as blues).

Let me fill you out on the historical context and the characters of Perry Bradford and Mamie Smith and on the impact of this famous recording session.

We are in the year 1920. The World War had ended and we are on the threshold of a decade that would be called the “Jazz Age”. Modernisation, urbanisation are key words. A dance craze was going on, and the ‘flappers’ (you see those ladies flapping their arms doing the ‘Charleston’?) and ‘sheiks’ were to defy the moral codes of their parents. The three major recording companies, Edison, Columbia and Victor did everything they could (especially Victor) to introduce the phonograph in the (white) middle- and upper classes. The aim was to place the phonograph (literally) next to the piano in the living room as a valuable piece of furniture. The 78-rpm proved at the same time a way for the parents to keep an eye (read : social control) on the dancing ‘excesses’ of their daughters : the dance music could be played at home which allowed their offspring to stay at home instead of going to the dancing halls which were regarded upon as places of moral decay.

Black musicians were marginalized. It was rare that a black musician was being recorded (examples as G.W. Johnson and clarinetist W. Sweatman only confirmed the rule), and black orchestras often imitated the white bands to get connected with the mainstream and to suit the audiences. At the same time, white orchestras frequently sought their inspiration in the African American musical style and music sheets. Vaudeville was popular; an artist as Sophie Tucker painted her face black and was popular as ‘coon shouter’ : she even hired some of the best African American singers of the time to give her lessons, and asked African American composers to write songs for her act.

The patent on the lateral cut recording which Columbia and Victor controlled had expired and this opened opportunities for other recording companies to enter the market using this “most recent” technology. This was however not an easy thing since the big 3 had managed to occupy the full market and could pay the highest prices for their contracts.

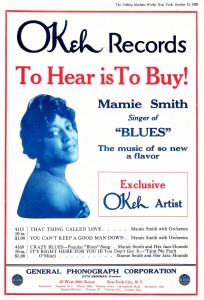

One of the newcomers was the Okeh label which understood that if it were to be successful, it had to be inventive and dig out some new consumer markets (blacks? women? black women ?). It was in any case inventive in its technology offering products that were compatible with both the lateral and horizontally cut records.

The label “Okeh” stood as an abbreviation for the initials of its founder Otto K. E. Heinemann (1877–1965), a German-American manager for the U.S. branch of German Odeon Records. Heinemann thought it would offer lucrative opportunities to dispose of an American based company given the war that was going on in Europe. He incorporated the Otto Heinemann Phonograph Corporation in 1916 and set up his own recording studio and gramophone pressing plant in New York. In September 1918 he was ready to start selling his products.

The ambition of Okeh to eat a piece of the recording market cake crossed the aspirations of the African American Perry Bradford (1893-1970) , composer, songwriter and also vaudeville performer working in New York since 1909. He had started in the minstrel shows already in 1906 and had played as a solo pianist (teenager) in Chicago 3 years later. Bradford was annoyed with the marginalization (read : discrimination) of blacks and their music on the cultural and recording stage, and was strongly convinced that there was a market out there for African American consumers to buy their own cultural products. In this, he built further upon a statement already published in 1913 in the “Chicago Defender” (popular ‘black’ journal) which following a ‘market survey’ concluded that records could be sold to the African Americans.

The ambition of Okeh to eat a piece of the recording market cake crossed the aspirations of the African American Perry Bradford (1893-1970) , composer, songwriter and also vaudeville performer working in New York since 1909. He had started in the minstrel shows already in 1906 and had played as a solo pianist (teenager) in Chicago 3 years later. Bradford was annoyed with the marginalization (read : discrimination) of blacks and their music on the cultural and recording stage, and was strongly convinced that there was a market out there for African American consumers to buy their own cultural products. In this, he built further upon a statement already published in 1913 in the “Chicago Defender” (popular ‘black’ journal) which following a ‘market survey’ concluded that records could be sold to the African Americans.

Perry Bradford must of worn out quite some pairs of shoes promoting his idea and pursuing his ideals, going from one record company to another. But his idea to open the record markets for Blacks and to value their music in its own right was perhaps a little too revolutionary. His persistence earned him in any case the nickname ‘Mule’. It was his dream of having a blues song waxed and he set everything to it to realise this dream, even if on the New York music scene he met a serious lack of interest, to say only the least. He remembered in his biography : “Whenever I began drifting into the lowdown, melancholy strains of the levee-camp ‘jive,’ someone would yell to detract my attention,” “Anything to keep me from whipping out those distasteful blues.” (quoted on : http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=6473116) The urban, black population just didn’t want to get reminded of the ‘old’ blues that was perfumed with the odors of slavery.

But then, one day, he found a listening ear in the person of Okeh’s musical director Fred Hager, after having been rejected from an audition at Victor’s studios some months before. “There are fourteen million Negroes in our great country,” Bradford told Hager, “and they will buy records if recorded by one of their own, because we are the only folks that can sing and interpret hot jazz songs just off the griddle correctly.” Hager was willing to go along. However, he wanted to bring in Sophie Tucker, a white singer, but Bradford pleaded to consider giving a black singer the chance. This Black singer, Mamie Smith, his ‘protégé’ was also an experienced entertainer coming from the vaudeville scene.

Coincidence, stubbornness and sheer courage shook hands in history. Coincidence, as Sophie Tucker fell ill for the scheduled recording. Stubbornness from Bradford’s side for his persisting energy to record black music by black musicians. Sheer courage and guts from Fred Hager for taking the financial risk in an environment which was severely hostile to black recordings. He received many threatening letters from some Northern and Southern pressure groups warning him not to record a colored girl. As Harry Pace would later experience, this threatening was not to be taken lightly as he was confronted with an attempt for bombing in the Black Swan pressing plant.

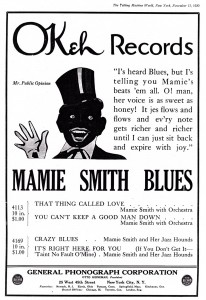

The first issue consisted of the combination of “That Thing Called Love” / “You can’t keep a good man down”, popular songs written by Bradford with a jazzy feeling to it. Mamie Smith was backed by a white group of musicians.

The first issue consisted of the combination of “That Thing Called Love” / “You can’t keep a good man down”, popular songs written by Bradford with a jazzy feeling to it. Mamie Smith was backed by a white group of musicians.

Its success was enough to convince Fred Hager to take it a step further and with Ralph Peer supervising the session, Mamie Smith entered the studio on Tuesday 10 Augustus 1920, with a group of experienced black musicians that – after having had a decent nip of liquor – recorded during several hours and after quite a few trials the songs “Crazy Blues” and “It’s Right Here For You”

The record sales were impressive. Literature indicates figures in the range of 10.000 in the first week and some 75.000 in the first month (Lawrence Cohn, 1996).

It is said that the song ‘Crazy Blues’ could be heard coming from the open windows of virtually any black neighborhood in America and that it was an important stimulation for the selling of phonographs : often the phonograph was bought with just this record in mind.

In any case, the way was paved for other companies to start recording other female blues vocalists and the first phase of the blues recording history was started. The conclusions of the ‘Chicago Defender’ in 1913 proved to be true, and money was to be made from opening the market for black artists and consumers.

What if Sophie Tucker would not have been ill? What if Mamie Smith would not have had the chance to record ‘Crazy Blues’?

As I said at the start of this article, this speculation is the fun part of history exploration : I leave it up to you to bring your guesses forth. Fact is that we have a rich legacy of several thousands of blues recordings in the 20s and 30s, even if they have been recorded by white entrepreneurs who were completely ignorant of the true cultural value of their products.