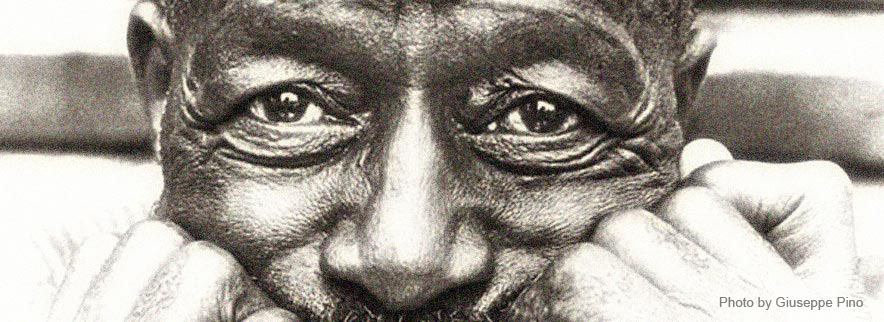

I have been reading a lot about the origins of the blues so far, and most of the literature presents quite interesting theories, but I was particularly struck this week with an excerpt from the classic work of Alan Lomax: “The land where the blues began” (pp 459-479). No theories, just a conversation between men who have lived it all. Lomax reports how he got to meet Sonny Boy Williamson (I – John Lee Curtis – the ‘original’) and Memphis Slim through his friendship with Big Bill Broonzy. In 1946 he had invited the three musicians to New York to perform in a production of his at the Town Hall in New York. To save them the cost of the hotel, he had invited them to sleep at his place. On a Sunday afternoon, they had reserved a studio at Decca’s where they could register some music together. However, things didn’t went exactly as predicted, and what came out of that afternoon session is one of the recordings that should be part of each serious blues aficionados’ collection, not for the musical content (which is more than satisfying – how else could it be with 3 artists of that caliber!), but in the first place for the conversation they had around the only microphone present.

Considering that the three men came from the South, from the period that the blues was in its ‘infancy’, he put them a very simple question: “Tell me what the blues are all about”. For the next two hours, Lomax didn’t need to speak another word. In the conversation that he recorded, during which the bottle of bourbon was passed several times, one gets a more than realistic story of how the blues originated. Sonny Boy Williamson having worked principally on the farm, the story about the work at the levee and rail road and other camps comes in the first place from Broonzy and Slim. The way the story is told however gives you goose skin: the terrifying stories are told throughout loud laughing as if the laughing serves a cathartic purpose which allows them to absorb the past mentally. They laugh the blues out of their lungs in a healing way, as “if they shared some old joke”.

I merely want to quote hereunder some passages which speak for themselves, and tell more about the way that the blues originated and evolved in terrible social conditions than a shelf full of books ever could do.

“Yeah, blues is a kind of revenge. You know you wanta say something, you wanta signifying like – that’s the blues. We all have had a hard time in life, and things we couldn’t say or do, so we sing it.”

“He couldn’t speak up to the cap’n and the boss, but he still had to work, so it give him the blues, so he sang it – he was signifying and getting his revenge through songs.”

“They’d crack you cross the head with a stick or maybe kill you. One of those things. You just had to keep on working whether you was tired or not. From what they call ‘can to can’t’. That mean you start to work when you just can see, early in the morning, and work right on till you can’t see no more at night.”

“In the meantime, if you were a good worker, you could kill anybody down there, so long as he’s colored. You could kill anybody, anywhere. You could kill anybody down there as long as you kill a Negro! Any Negro. If you could work better than him. Don’t kill a good worker – then you were sorry. If you did, you go to the penitentiary.”

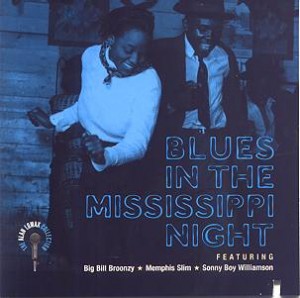

The story didn’t end there. What happened after this famous recording gives even more depth to their words. When Lomax let them hear what they had told during their conversation, the men wanted Lomax to destroy the recordings. Luckily, Lomax convinced them otherwise, but only on the condition that their names would not be revealed because they feared that their lives and the lives of their relatives would be in danger when their words were heard in the South. The trialogue was first published on paper in 1948 using fictitious settings and names. The recording was issued on vinyl in 1959 (“Blues in the Mississippi Night”) maintaining the fake names, and Lomax only put a name to the voices in 1990 when a CD-version was issued. Sonny Boy Williamson had died already in 1948 following a street mugging. Broonzy had died on August 15th 1958 (10 days before I was born, by the way) following throat cancer and Memphis Slim had passed away in Paris in 1988 after a successful career on the European continent.

I had a hard time finding the sound recording because the CD seems to be sold out everywhere, but luckily I managed to track it down in digital form via a small independent internet store. I treasure it as nothing else.