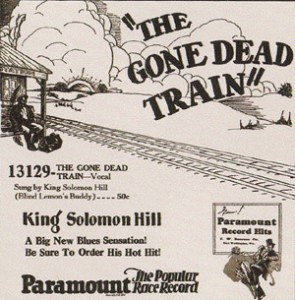

The 22nd episode of the ninth season of the popular CBS-series CSI, Crime Scene Investigation was called “The Gone Dead Train”. The title refers to a blues song recorded by King Solomon Hill for Paramount in 1932, a song which is also played in the episode. I’m puzzled by the relation (if any) between the song and the topic of the series (an investigation on a serial killer who uses rabies as his murder weapon), especially if one explores who King Solomon Hill was. Perhaps the producers of CSI were lead by Randy Newman’s ‘Gone Dead Train’, but the songs are clearly different.

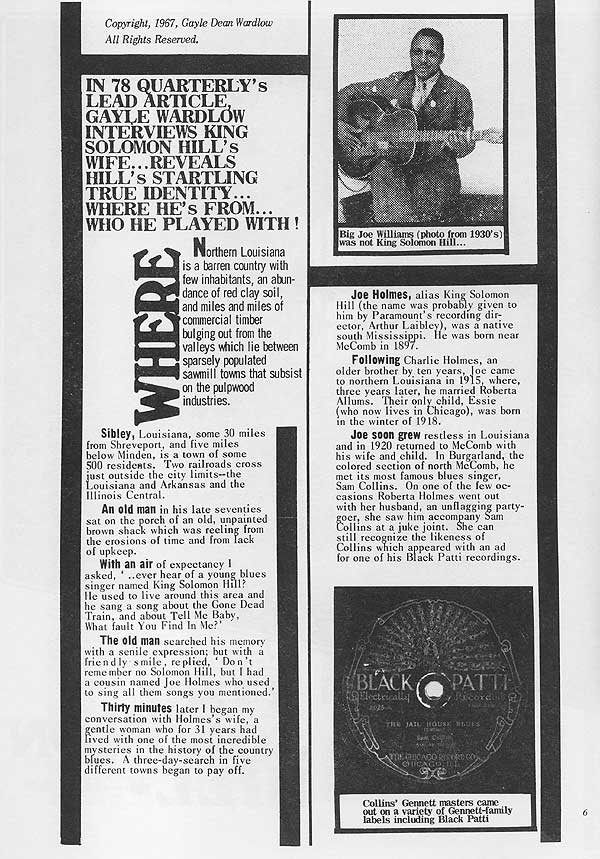

King Solomon Hill is sometimes considered as merely a footnote in the history of the blues, and yet I believe he deserves more than a solid chapter. The problem however is that very little hard facts are known about this man, so it would be rather difficult to fill this chapter with biographical data. Much more is to be said – other than on his musical output – about the fog that surrounds the figure and especially about the way that history and its writers have tried to clear this fog. In fact, the identity of the man has been the subject of some heated debate between different writers, a debate which partially reflects the piecemeal and divergent approaches to clarifying the blues history. In his famous ‘The Country Blues’, Samuel Charters asserted in 1959 that King Solomon Hill was a nickname for Big Joe Williams, a blues singer and composer, born in 1903. Big Joe Williams played the Delta blues, and developed his own particular style which made him particularly popular during the folk-blues revival in the 50s and 60s. This popularity might be connected to Charters’ assertion.

Notwithstanding the intensive field recording work done by Samuel Charters, his assumption on the identity of King Solomon Hill was based on quicksand and was contested in the mid 60ties by researcher, journalist, record collector and later world authority on pre war blues Gayle Dean Wardlow (the article has been published in the famous 78 Quarterly, n° 1, 1967 – a magazine that is as rare to find as the 78rpm which it deals with). Based on a geographical hint in the lyrics of “The Gone Dead Train”, he tried to locate King Solomon Hill, but only found a handful of people who had known a certain Joe Holmes who had this song on his repertoire. One of those people was Roberta Allums who had been married to Holmes, though their marriage had never been much of a success.

From the information gathered, Joe Holmes must have been a figure who typically fitted the cliche image of the bluesman : a wandering hobo, smoking and drinking heavily, and going around to different places and juke joints to try to earn as much money as possible, avoiding hard work. During his roaming he seems to have met and played with Big Lemon Jefferson, and had developed a playing style that drew from Ramblin’ Thomas and Sam Collins (Salty Dog Sam) who had a similar characteristic combination of a falsetto singing with dazzling slide guitar. Other than his draft card for the army, no documents seem to have been found on Joe Holmes. No birth certificate (born in the region of North Louisiana, South Mississippi 1897), no death certificate (1949).

In 1932 he has been invited to Grafton, Wisconsin (north of Chicago) to record (along with another bunch of blues men) for Paramount for which this and other recordings in the early 30’s (a.o. Son House & Charley Patton 2 years before) must have been a desperate act of survival (Paramount collapsed shortly after, as I wrote in an earlier post). There is trace of 6 songs only, and until 2002 only 4 of them had been found on record. A (unique) 78rpm of the 2 others only popped up some ten years ago.

After his recordings, Holmes went out on the street again, playing. His heavy drinking and smoking probably shortened his life : he died (as his wife told) after a hemorrhage without wanting to see any doctor. It wouldn’t be surprising thus if no death certificate has been made up at all.

Wardlow’s assertion was very soon after his initial publication criticized, but no counter proposals have been brought forth meanwhile which contradict his theory that King Solomon Hill was the alias used by Paramount in 1932, a nickname based on the geographical home basis of Joe Holmes (there still exists a Baptist Church of King Solomon Hill). We all know that Paramount was not very strict on the names they gave to its artists, often issuing the work of one artist under different aliases.

The story on Joe Holmes illustrates in my opinion two things : (a) there is no correlation between the volume and success of the output of a musician and his/her artistic achievement, and (b) by lack of coordination lots of efforts have been spent wrongly in the query of the historical trails of the blues.

(a) Artistically, the six songs waxed by Holmes – even if not all of them were his composition – are each of them considered as masterpieces, especially his “The Gone Dead Train”. His singing and his guitar playing (with a bottleneck or a bone rib) had never been heard before, or has ever been repeated afterwards. He is without any doubt of the same league as Son House and Robert Johnson. Nevertheless, everything points out that no more than a handful of his records have ever been sold. He stands out though as an immensely creative and original artist (listen for instance to his The Gone Dead Train here).

(b) The blues has been the subject of much attention, but this notice has been dispersed and uncoordinated. Already in the early beginning it has been the subject of scholarly inspired field work by a.o. father and son Lomax. At the same time, record companies were eagerly looking for black country blues artists in their efforts to cope with the competition of the radio medium. Different talent scouts were on the road, one not knowing what the other did, let alone that they were aware of the scholarly interest in the blues. God only knows what would have come out of the combination of both. We can only dream…

The blues revival from the late 50ties and 60ties – inspired by the white country folk interest – approached the subject more from an idealistic point of view, lead by the noble goals of the civil right movement that highlighted the discrimination to which the black population had (was) been the victim. Myths and and romanticized cliches on the black blues country singer stood often in the way of obtaining a realistic image of what really happened. One might even say that despite their noble objectives, the blues revival was more or less mislead by the filters that the record companies in the 20ties and 30ties had put on the musical output of the black culture. I think it was not appropriate during the early blues revival to claim that before the blues was waxed there existed a common pool of music that was to a large extent racially mixed. Record companies had heavily bet on the ethnic and racial segregation of the market (see also : Recorded Music in American Life, The Phonograph and Popular Memory, 1890-1945, W.H. Kenney, Oxford U.P. 1999).

This mythical view has been challenged, luckily, by empiric field research as the one done by Gayle Dean Wardlow who went looking for the testimony of people who had known the artists, or used their journalistic experience to scrutinize administrative archives. Facts prevailed on myths. Even if some combined the detective work with a financial interest to find rare 78 records that would become worth a fortune, their efforts in unraveling the sound played in the juke joints and the streets in the 20s cannot be overestimated.

But of course, all of this does not explain why the CSI-producers used the title of a blues song by an obscure figure in the mist of early blues times for one of their episodes. I have contacted CBS but didn’t receive any feedback yet. If I get a reaction, I will surely update you on it and this would be my humble contribution to history…LOL.

Article in PDF-format : The blues in CSI (Crime Scene Investigation)